National Societies have a clear understanding of the interlinked political, social, cultural and economic aspects of the evolving operational environment and the inherent risks, which forms the basis for preventing and managing those risks.

In sensitive and insecure contexts , including armed conflict and internal disturbances or tensions, certain groups or individuals will control or influence your ability to reach people in need promptly and safely. Therefore, it is essential to understand the operational environment and the underlying political, social, cultural and economic factors that define it. Knowing the history and root causes of the tensions, the power dynamics and who is fighting whom, why, where and with what weaponry is essential if you are to provide a safe and effective response.

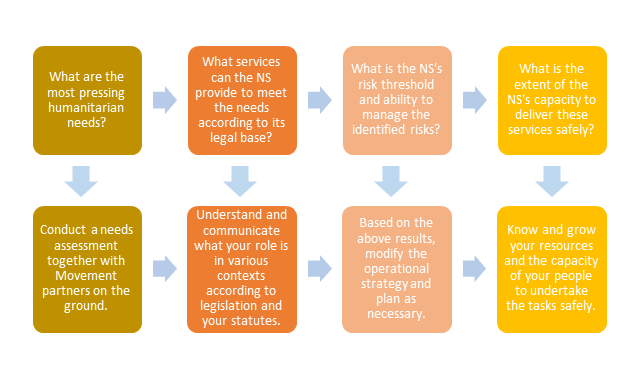

Any situation where unmet humanitarian needs exist gives cause for the National Society (NS) to reflect on whether or not it has the mandate and capacity to respond.

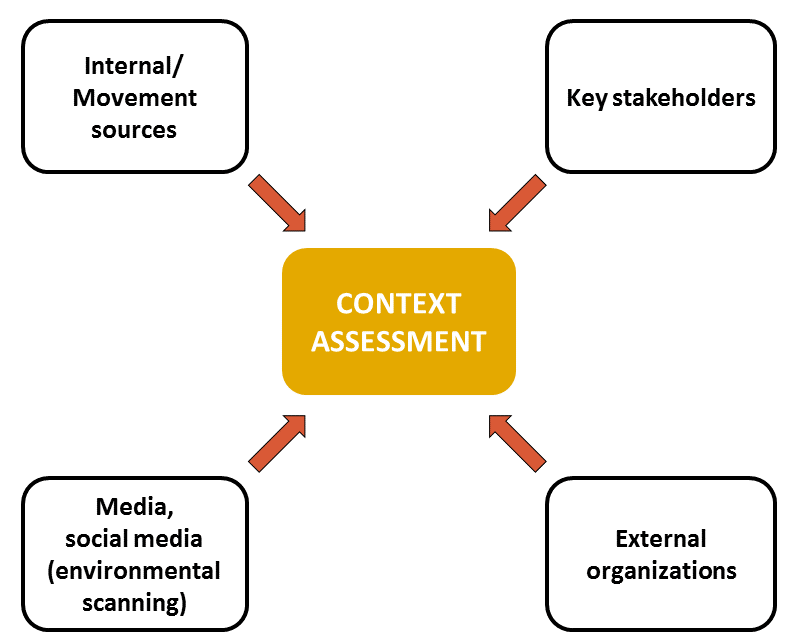

The stages of assessment shown in the diagram are interactive and dynamic, occurring concurrently and continuously for the duration of the event. It is essential to have an ongoing mechanism for context assessment in place at all times in order to detect and anticipate events and their potential humanitarian consequences. The results of the assessment inform the decisions and actions of the National Society and enable it to address risks and better inform, prepare and train staff and volunteers to respond safely to any challenges they face.

The stages of assessment shown in the diagram are interactive and dynamic, occurring concurrently and continuously for the duration of the event. It is essential to have an ongoing mechanism for context assessment in place at all times in order to detect and anticipate events and their potential humanitarian consequences. The results of the assessment inform the decisions and actions of the National Society and enable it to address risks and better inform, prepare and train staff and volunteers to respond safely to any challenges they face.

Context and risk assessment is reliant upon the gathering of adequate, accurate and reliable information, and is the foundation of all other aspects of maintaining and increasing your acceptance, security and access.

1Action checklist

Understand how a given sensitive and insecure context affects different sectors of the community and how your National Society and the rest of the Movement will respond.

Establish a permanent context and risk assessment system that includes monitoring of evolving trends and challenges, including threats and risks to your personnel and assets and to the people you serve.

Assess the capacities of your National Society to reach and to meet the needs of those affected in a way that pre-empts or mitigates the evolving risks.

Develop and refine response and contingency plans to address the specific challenges you are most likely to face in a sensitive and insecure context.

2Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction

Sensitive and insecure contexts have certain characteristics that influence who is likely to be worst affected, their needs and how the National Society and its Movement partners should best respond.

For instance, the presence of armed groups or actions by other stakeholders may result in access to affected people and communities being controlled or restricted and may pose security risks to a National Society’s personnel and assets. In such situations, additional preparedness steps and a different way of working are called for.

It is important to understand the similarities and differences between preparing for and responding in disasters and in contexts featuring violence or the threat of violence. This will greatly influence whether and how a National Society will be able to respond effectively and safely.

Context assessment and stakeholder mapping

The starting point is to establish a process for gathering and analysing historical, political, social, cultural and economic information, trends and challenges from a variety of sources, which will form the basis for your context assessment. This process must be continuous as the context is constantly evolving.

Did you know ?

In sensitive and insecure contexts, there are distinct features to incorporate into your context assessment. Where armed groups or other stakeholders are present, it is essential to build an objective understanding of the history and nature of the dispute or violence. What are the root causes of the tensions or conflict? How has the situation evolved over time? Who are the stakeholders? In other words, you need to know who is fighting whom about what, where, why, and using what tactics and means.

Why? You could not risk deploying your response teams in an insecure situation without knowing as much as possible about the nature of the event and the stakeholders involved so that you may employ the appropriate risk-avoidance, prevention and mitigation measures.

Also as part of the context assessment, you will need to conduct an ongoing mapping and analysis of the various stakeholders who control or influence the operational context and your security or access. These can be numerous, with groups shifting alliances and regularly changing leadership. The information collected can be quite extensive and confusing unless it is systematically organized. There is a strong link here to “External communication and coordination”, section V, as this mapping exercise feeds not only into the context assessment but also into the associated communication plan targeting these stakeholders.

Mapping stakeholders and their interests is sensitive to undertake and even more so to document. It may be perceived by some as overly political. However, remember the purpose of the exercise is solely to plan and implement your humanitarian response safely and effectively. The information must therefore be gathered and handled with care.

Your sources of information must be reliable and your analysis continually updated as this will guide your decisions, such as who you can deploy safely, when and where. Confidentiality guidelines must be in place and reinforced as it is essential to handle sensitive data in a way that ensures it is not widely shared or used publicly or in an inappropriate manner. It is always useful to have a collective approach when conducting your assessment and analysis, engaging key individuals in your organization at various levels, particularly from branches and response team leaders, where they are exposed to the daily realities, and from within and outside the Movement.

Once the context and risks are assessed and the needs and existing capacities of the affected population and of the National Society are better known, the National Society must reflect on its mandate and roles, as enshrined in legislation and its own statutes, to ensure it acts in accordance with these instruments and fulfils its auxiliary role to the public authorities in the humanitarian field. When taking action grounded in its legal base and supported by the authorities and other stakeholders, a National Society is on a firm footing and can use this status as a tool to gain or enhance access. (See also Legal and Policy base, section II.)

Risk assessment

On the basis of the evolving context assessment and in accordance with the National Society’s legal base, an ongoing operational risk assessment needs to be conducted. In a sensitive or insecure context, the National Society faces a broad range of threats, including violence, conflict, natural hazards, health issues, political interference, crime and corruption. It must therefore analyse which threats are present in a particular environment, the extent of the risk they pose to National Society personnel and assets, and which ones are within their defined risk threshold.

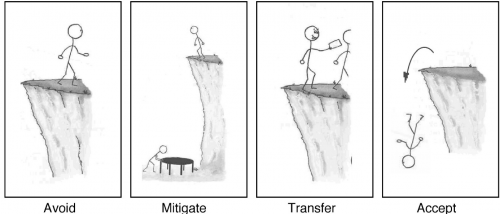

Risk assessment should be an integral part of your operational response or programme design. Strategies have to be developed to avoid, prevent or reduce the National Society’s exposure to risks, or even, in some cases, transfer the risk to others who may be less exposed or better equipped to manage the risk. Ultimately, the National Society’s tolerance or threshold for risk must be defined by management and its ability to manage these risks assessed.

It is useful to develop in advance an operational plan and a contingency plan to address possible scenarios, based on the information gathered for the context assessment and adjusted according to the evolving context and accompanying risks. It is essential to do this in tandem with other Movement components active in your context to ensure the inclusion of diverse perspectives which will increase the quality of the plan and, consequently, maximize the impact and reach.

Capacity to undertake context and risk assessment

It is essential to be systematic and professional in carrying out a context and risk assessment in today’s often complex insecure contexts. Establishing a system, tools and templates, and even training to ensure robust implementation in practice, is recommended. The present Safer Access toolbox will provide some guidance in these areas.

The Movement dimension

In insecure contexts, it is particularly beneficial if the ICRC and the National Society collaborate closely on the formulation of the context and risk assessment. In settings where several Movement partners are present, all information must be shared openly and in a timely manner, and the partners invited to contribute to its analysis, based on their contacts, perspectives and experiences.

1Guiding questions

- Are you aware of the similarities and differences between preparing for and responding in disasters and in contexts featuring violence or the threat of violence in terms of the needs, risks and manner of response?

- What system is in place and who is involved in gathering and analysing information on emerging political, social, cultural and economic trends that could influence humanitarian action? How is this knowledge used to guide your preparedness and response?

- What system do you have for continuously incorporating new data into your evolving context assessment and feeding it into your operations?

- How do you decide on the credibility and reliability of your information sources?

- Who are the key individuals, groups, organizations, State institutions and other stakeholders that can affect your security and access? What is their political and/or social position, power, background and perception of your organization?

- What system is in place and who is involved in conducting your ongoing risk assessment? What is your organization’s tolerance level for various types of risks? What would you not tolerate?

- Have you assessed and developed your National Society’s capacity and ability to manage identified risks? How can you improve your ability to undertake this essential task?

- Does your contingency plan build on community self-preparedness and protection practices and take account of specific anticipated scenarios?

- How do you ensure your operational, contingency and security plans are current, integrated, relevant, known and followed?

1.1 Characteristics and challenges of working in sensitive and insecure contexts

The similarities and differences between preparing for and responding in disasters and in sensitive and insecure contexts, including armed conflict and internal disturbances and tensions, are understood in relation to: (1) the evolving operational environment; (2) humanitarian needs; and (3) the nature of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement response; this knowledge is used to update preparedness and response measures.

Safer Access: A Guide for All National Societies contains an excellent summary of the distinctive features of sensitive and insecure contexts. It is essential knowledge for anyone working in such contexts and can be found on page 23 of the Guide. It is also important for people in leadership positions at all levels of a National Society to understand how these features might affect the way they prepare for and conduct themselves during a response.

The reality today is that there are potential sensitivities in almost every area of our day-to-day work, which, especially in insecure contexts, may compromise our security and access. It is vital to be vigilant at all times so that appropriate action can be taken to identify and overcome these challenges. When “gatekeepers” (persons or groups, armed or unarmed, who influence or control access and security) are present, it is important to know who they are, their leadership and power structure, and their methods and tactics. This will help in developing appropriate communication and negotiation strategies.

Each context, regardless of how it is characterized or defined, is distinct and must be analysed thoroughly and the response adapted accordingly.

The table below is a condensed version of the one found on pages 28–29 of the Guide.

|

Characteristics and challenges of working in sensitive and insecure contexts |

|

|

|

Distinctive features |

|

Context

|

|

|

Needs |

|

|

Response |

|

1.2 Emerging trends and challenges

Emerging political, social, cultural and economic trends and challenges that may affect humanitarian action are explored and analysed and this knowledge is used to guide preparedness and response.

The multiplication of public information sources and rapid advances in information technology have increased the need to better understand the complex local, regional and global environment in order to avoid surprises, anticipate risks and develop appropriate operational responses and communication strategies. Environmental scanning is one of the tools that contribute to this general context analysis.

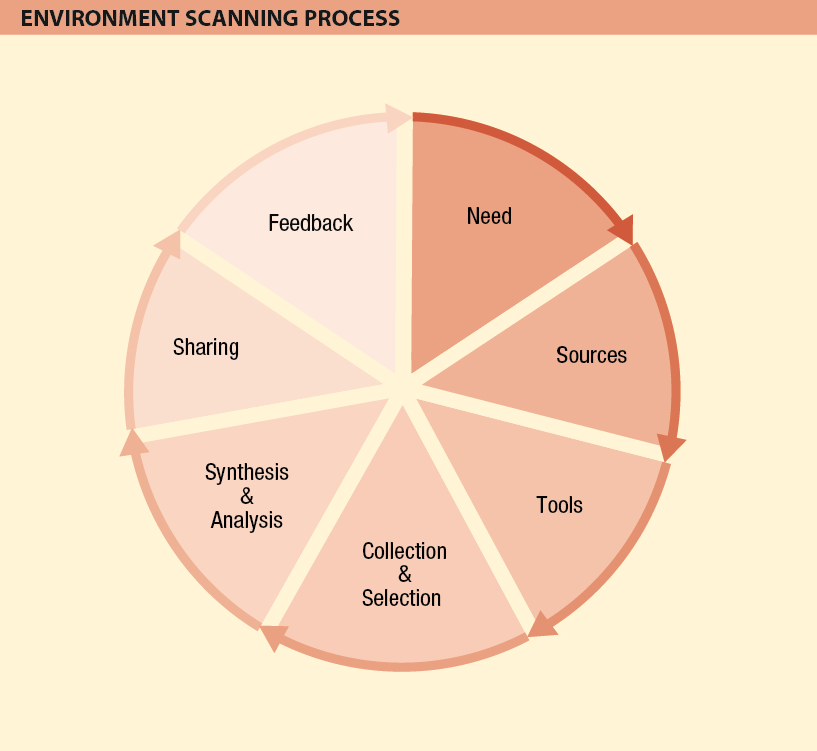

Environmental scanning is the proactive process of selecting, analysing and sharing publicly available information in order to support operational or strategic decision-making. There are seven stages in the process: needs assessment; identification of relevant sources; selection of appropriate tools; collection and selection of key pieces of information; synthesis and analysis of the information; sharing of the information analysis; and gathering of feedback.

In order to gain a comprehensive and balanced reading of a situation or issue, it is important to draw on a broad range of sources reflecting a wide variety of perspectives, including not only traditional and social media, but also the output of think-tanks, academic literature and international and non-governmental sources. With a particular focus on novelty, change and debate, environmental scanning aims to identify and analyse trends and emerging issues that are of interest or that may affect the humanitarian response. Trawling through vast amounts of public information also helps to detect early signs of opportunities or threats.

Did you know ?

- Having a structured approach, with one person acting as a focal point to coordinate and liaise with management, will considerably aid data collection and analysis.

- Using the “5 Ws & H” (who, what, where, when, why and how) technique will help you to pinpoint the specific information required.

- Applying systems to assess the reliability of sources will ensure the credibility of the information gathered.

As reputation issues online can have a direct impact on the security of operations on the ground, it is vital to constantly monitor how the components of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement are portrayed in the media in order to understand and analyse how the Movement as a whole, as well as its individual components, is positioned and perceived in the public domain. This focused monitoring specifically aims at anticipating, detecting and mitigating potential reputational issues, identifying key critics or supporters worth engaging with, and flagging opportunities and risks to communicate.

The information analysis should comprise both quantitative and qualitative aspects. The number of articles on a given subject provides an idea of the volume and its evolution over time (quantitative aspect), while the nature of the source, the tone, and the type and quality of the coverage, as well as other elements that qualify and contextualize the information, will indicate the reliability of the information (qualitative aspect).

In the digital age, when anyone can post freely on social media, one of the main challenges is the verification of information in order to filter out misinformation, rumours, hoaxes, fake accounts and all types of erroneous, manipulated information. Online ethics and security is another difficult area as environmental scanning often entails consulting sources that express controversial or extremist views and opinions. Depending on the context, the monitoring of these can involve medium to high risk. It is therefore important to ensure a safe and legal online presence and behaviour when scanning.

Monitoring tools facilitate both the scanning and the collection of relevant pieces of information. Free tools such as Netvibes and Hootsuite offer great possibilities to set up a professional environmental scanning system, while paying subscriptions to Radian 6, Brandwatch or Meltwater allow for more in-depth analytics of traditional and social media content.

1Action checklist

- Allocate adequate resources to carry out the environmental scanning function.

- Clearly identify information requirements through consultation with the “end user” (management).

- Use the “5 Ws & H” technique to fine-tune the needs.

- Use a system to select and validate the credibility and reliability of your information sources and data.

- Collect relevant data according to established criteria and requirements.

- Synthesize and analyse the data collected; summarize it succinctly and present it in an easy-to-read manner.

- Share it electronically; be prepared to orally present it as necessary.

- Obtain feedback on the relevance and presentation of the data.

1.3 Context assessment

A permanently evolving context assessment is developed and maintained so as to ensure a thorough understanding of the operational context as well as of the stakeholders and the affected people and communities with their specific assistance and protection needs. (See also VI. and VII. Internal and external communication and coordination)

While the data gathered through an environmental scanning process contributes greatly to your context assessment, many other sources of operational information exist and must be factored into the overall assessment. These include:

- key stakeholders, who may influence or control your security and access;

- internal/Movement sources;

- communities and others.

Context assessment sources

In addition to an overall assessment of the context and situation, a specific and more detailed conflict and violence analysis is required in sensitive and insecure contexts in order to understand the roots of the tensions, including who is fighting whom for what reason, when, where, why and with what means. This is important as you could not risk deploying your response teams in an insecure situation without knowing as much as possible about the nature of the event and the elements involved so that you can employ the appropriate risk avoidance, prevention and mitigation measures.

1.4 Risk assessment

In accordance with the evolving context assessment and the National Society’s legal base, an ongoing risk assessment, which includes the communities’ preparedness and self-protection strategies, is conducted in order to establish a standard operational security risk management system and approach. (See also VIII. Operational security risk management)

Building on the information gathered and analysed through your environmental scanning and context-assessment processes, the next step in the establishment of your operational security risk management system is to gain a clear understanding of the threats and risks.

The risk-assessment process is an integral component of your project/programme design phase. In order to achieve project/programme objectives, the exposure to risk must be reduced, mitigated, avoided or transferred.

Threat

is any safety, security or other form of challenge to your staff, assets, organization, reputation or programming that exists in the context where you operate.

Risk

is a measure of exposure or vulnerability to threats, determined by their likelihood of occurring and level of impact on your staff, assets, organization, reputation or programming.ed by National Societies.

First, threats must be identified. Threats may or may not have any impact on the organization; in other words, they may or may not pose a risk to its staff, assets, organization, reputation or programming. Below is a list of potential threats in any given environment, taken from the European Interagency Security Forum’s Security to go: a risk management toolkit for humanitarian aid agencies, Module 3, Risk assessment tool (see Toolbox).

Violent threats

|

Organizational

|

Environmental

|

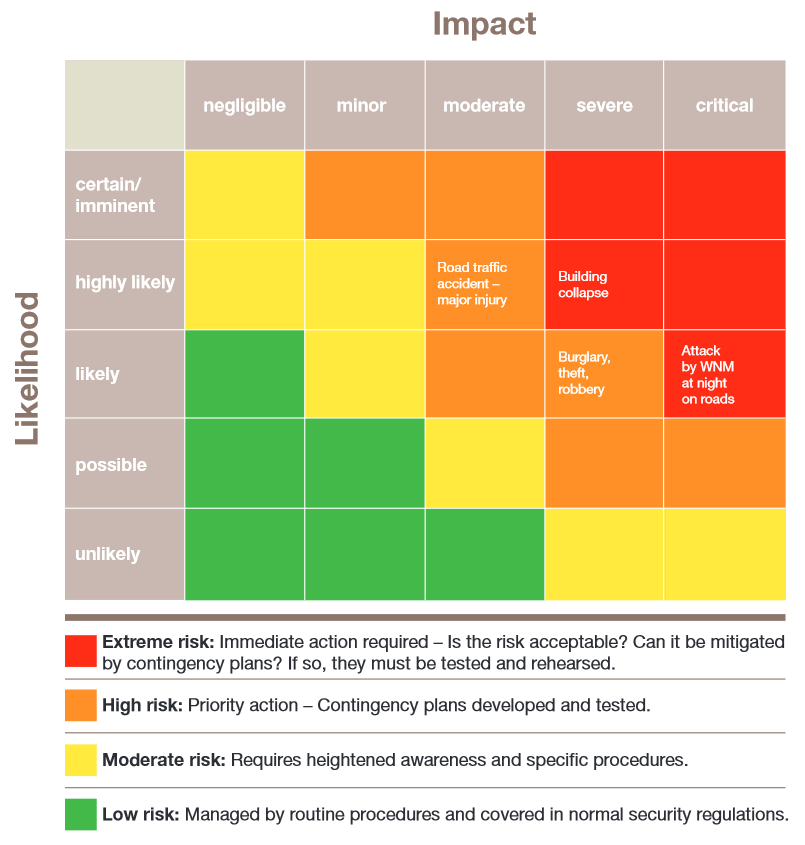

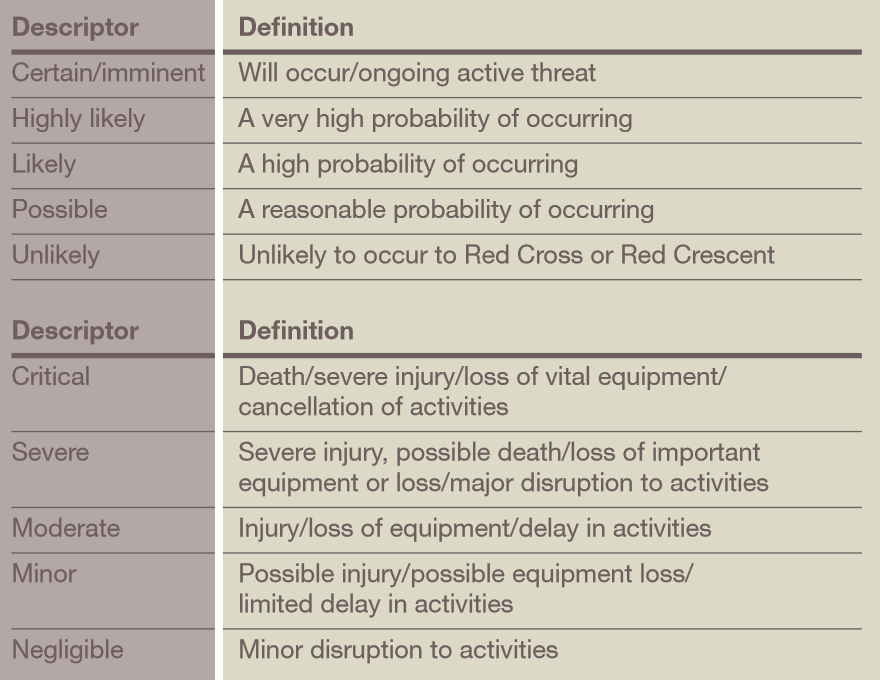

Once the threats are identified, they must be assessed in terms of their likelihood of occurring and the level of impact on the organization and its people and assets, from which is determined the actual risk to the organization. Strategies can then be developed to reduce, mitigate, avoid or transfer these risks.

A simple example: The National Society works in a part of the world where the airlines have a very poor safety record with frequent near misses and several incidents each year that cause loss of life. This is an easily identifiable threat. If a National Society does not allow its staff to use such airlines for travel, they have effectively removed the exposure to this threat, thus avoiding the risk.

A risk-planning matrix is helpful in plotting the level of risks. See the example below, which can also be found on pages 26-28 of the International Federation’s “Stay safe” publication.

Risk-planning matrix

By its nature, working in sensitive and insecure contexts goes hand in hand with risk. When plotting the risks on the matrix, you will need an understanding of the institutional risk tolerance. This is often referred to as “risk threshold” and must be intentionally decided upon by senior management. A certain level of risk is considered acceptable only if it is justified by the humanitarian impact of the operation. A balance must always be struck between the risk an action entails and its anticipated effect. Ask the question whether the impact of a planned activity is worth the risk it involves. If the answer is “no”, the operation or activity should in principle be suspended, postponed or discontinued.

Risk assessment is an area that is somewhat complex and where careful, systematic analysis is required. The data must be scrutinized by senior management and used to guide their operational decisions. See the Toolbox for some excellent reference documents to increase your understanding of this issue and to help you develop a system that works best for your National Society.

1Action checklist

- Identify and understand the threats in your context.

- Analyse the risk each of these threats pose to your organization’s personnel and assets by determining the likelihood of them occurring and the level of impact possible for your organization.

- Map the findings on a risk-planning matrix.

- Identify your organization’s risk threshold and assess the risks identified against this threshold.

- Make decisions on your operation using the “humanitarian imperative” and risk threshold as guides: what measures can you take to avoid, mitigate or transfer the risk?

- Decide whether to suspend, postpone or discontinue some activities in some locations owing to the unacceptable exposure to the risk.

1.5 Capacity to respond to the needs and manage risks

The National Society’s capacity and ability to manage the risks identified in sensitive and insecure contexts is assessed and developed. (See also II. Legal and policy base and VIII. Operational security risk management)

Many resources exist within the Movement to address the above questions and required actions. Concerning the capacity of the National Society to deliver services safely, the provides a broad overview of some of the systems, structures and tools required.

Sometimes, the actions and measures contained in the Safer Access Framework are not taken into account in a disaster-preparedness strategy. Yet, without these, a National Society may be hampered in its movements or access to people in need as they are not accepted by the persons or groups who control that access, and their security may be compromised by the lack of procedures in place to manage operational risks.

1.6 Contingency plan for sensitive and insecure contexts

A contingency plan which builds on community preparedness measures and takes account of specific scenarios is developed and refined in order to enhance the rapid provision of effective assistance and protection for people and communities.

The aim of contingency planning is to prepare an organization to respond well to an emergency and anticipate its potential humanitarian impact. A well-developed plan will answer three questions:

- What is likely to happen?

- What are we going to do when this happens?

- What can we do ahead of time to prepare ourselves?

Much of the information gathered during your context and risk assessment will help you structure and consolidate your plan.

Contingency planning for natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods or typhoons, should factor in the probability or likelihood of the added threat of violence or even conflict, which may inhibit acceptance, security and access to those affected. Moreover, specific contingency plans should be developed for events that are or have the potential to be characterized by insecurity or violence, often referred to as “socio-political hazards”. These include demonstrations, electoral violence, civil disturbances and outright armed conflict.

The plan should build on existing community-preparedness and self-protection measures and complement national plans. Whenever other Movement components are operating in your country, you would need to prioritize efforts to align your plan with theirs or develop a joint contingency plan in order to maximize Movement resources and thus reach more affected people more effectively.

An excellent guide to contingency planning can be found here.

To learn more about the actions and measures linked to this element, click on the button marked “Practical tools and reference materials” to access tools or on the “Safer Access in Action” map to read individual National Society accounts of the actions and measures they took when operating in sensitive and insecure contexts.

I. Context and risk assessment

I. Context and risk assessment